Why St. Paul UMC Is on a Soaring Trajectory

Richie Butler took an unorthodox path to Methodist ministry and revitalizes a historic church

St. Paul United Methodist Church is 144 years old — and a comeback kid.

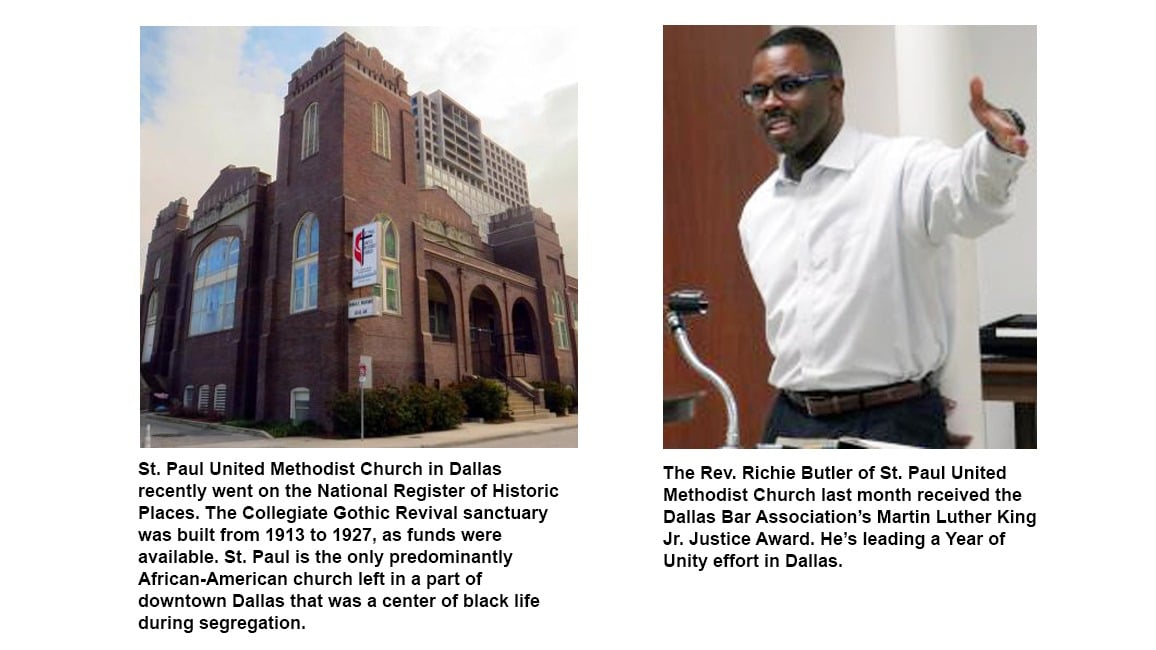

Even as it’s gained National Register of Historic Places status, this storied but small African-American church in Dallas is undergoing renewal.

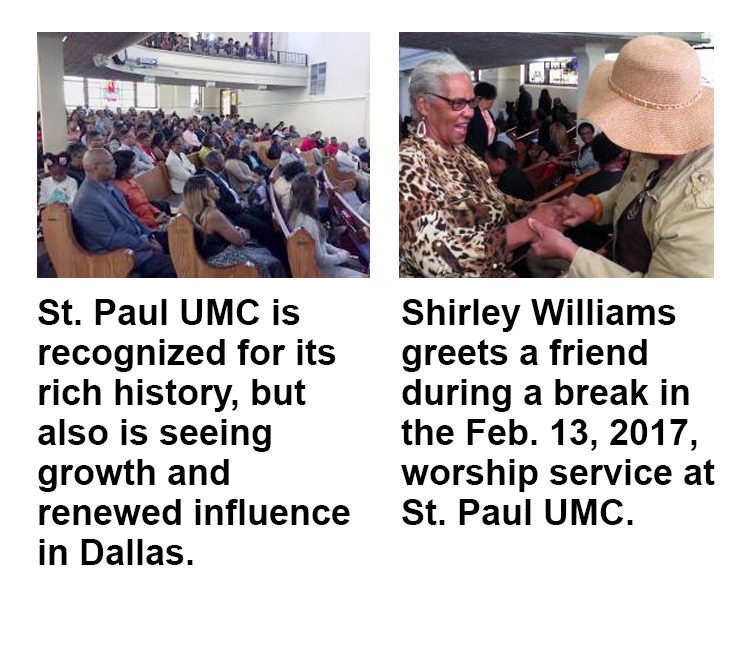

Attendance is up. Social outreach is brisk. And in the pulpit is the Rev. Richie Butler, who is winning local recognition as a race relations bridge-builder.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that the public witness of The United Methodist Church is stronger because of Richie’s presence and voice in the city of Dallas,” said North Texas Conference Bishop Michael McKee.

Butler, 45, has initiated a Year of Unity project, recruiting an interracial leadership team that includes former President George W. Bush, a United Methodist, as honorary chair.

The effort will, Butler believes, benefit Dallas while helping to raise St. Paul United Methodist’s profile as a community force.

“God has called this church not to become history, but to make history,” Butler said.

St. Paul United Methodist Church was founded in 1873 under a brush arbor, in the Freedman’s Town/North Dallas area, which would become a center of black life in segregated Dallas.

Construction on the current sanctuary began in 1913 and continued, as money was available, through 1927. The brick building is in the Collegiate Gothic Revival style, with towers and an intimate interior worship space, featuring stained glass, a balcony and curved pews on a main floor that gently slopes toward the pulpit and choir.

Construction on the current sanctuary began in 1913 and continued, as money was available, through 1927. The brick building is in the Collegiate Gothic Revival style, with towers and an intimate interior worship space, featuring stained glass, a balcony and curved pews on a main floor that gently slopes toward the pulpit and choir.

St. Paul was one of a handful of strong African-American churches in Freedman’s Town through the middle of the 20th century. Leading black citizens attended St. Paul, and it had renowned pastors, including the wonderfully named I.B. Loud.

The church provided space for a teaching training school that would become United Methodist-affiliated Huston-Tillotson University in Austin, Texas. The Dallas Bethlehem Center also began at St. Paul.

In the early 1950s, St. Paul provided internships for three of the first five black students at Perkins School of Theology, part of Southern Methodist University.

But the latter half of the 20th century saw the black community around St. Paul gradually disperse, due in part to a major highway that cut through the neighborhood. St. Paul is one of only three institutional buildings left of Freedman’s Town, and the only one serving its original purpose.

“It’s a historic urban church, and there aren’t many of those left,” said Rickey Johnson, a St. Paul member.

Indeed, St. Paul is the only predominantly African-American church still in greater downtown Dallas.

These days, St. Paul is in the city’s Arts District, steps away from major performance halls and across the street from the Booker T. Washington High School for the Visual and Performing Arts.

With financial help from nearby Highland Park United Methodist Church, St. Paul underwent a major renovation in 2009-10. The sanctuary is a small but swinging part of the Arts District, hosting jazz concerts monthly.

But thriving as a church has been a challenge, given the neighborhood’s transformed demographics.

Enter Richie Butler.

Butler grew up on the east side of Austin, in a single parent household. He attended SMU on a football scholarship.

From there he went to Harvard Divinity School, taking finance and urban planning courses on the side.

Butler settled in Dallas, making real estate development his day job, while preaching on Sundays. He worked with the local African-American Pastors’ Coalition in building new single-family housing in the city’s embattled south side.

In 2002, Butler started a nondenominational church while continuing in business. He came to know McKee through their service on the Perkins executive board and later the SMU trustee board.

The bishop recalls asking Butler why he wasn’t a United Methodist.

“He replied no one had ever asked him,” McKee said. “Our conversation began then.”

Their talks would lead, in 2014, to Butler’s merging his church into St. Paul and accepting McKee’s invitation to become a United Methodist and St. Paul’s pastor.

“My first Sunday I preached there, I felt at home,” Butler said. “I know this is where God called me to be.”

Butler has continued to be a bi-vocational pastor, working during the week at the Prescott Group real estate and investment firm. But he’s on a path to fulltime ministry.

Under him, St. Paul has grown from about 130 to 200 in Sunday worship, according to North Texas Conference records. The church’s ministries include Body & Soul, which feeds the homeless on Saturday, and a developing program for providing shelter to homeless women.

A recent Sunday showed St. Paul still has plenty of tradition, including singing “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” Male ushers wore formal suits, and some women in the pews wore hats.

But Butler himself wore a blazer and jeans, and joined in standing and clapping as a praise band jump-started the service.

Butler’s sermon included a call for church members to become more intentional in Christian discipleship, in part so St. Paul can grow.

“We want to double our size in the next three to five years,” Butler said in an interview after a Wednesday night Bible study.

The National Park Service placed St. Paul on the National Register of Historic Places on December 27, 2016, acting on a richly documented application by architectural historian Diane E. Williams.

About two weeks later, the Dallas Bar Association gave Butler its Martin Luther King, Jr. Justice Awardfor his work on improving race relations.

For the last couple of years Butler has, with the Rev. Andy Stoker of First United Methodist Dallas, hosted a Friday morning phone call for local pastors in which they candidly discuss race and other issues, and pray together.

Butler also started what’s becoming a tradition of basketball games between Dallas police and local pastors. His Year of Unity plans include a mass pulpit swap, with pastors preaching in a church that’s predominantly a race other than their own.

“Every single visionary move that Richie makes seems to fall in line with exactly what our city needs,” said Stoker.

St. Paul’s celebration of its National Register of Historic Places status is some months off.

But for longtime member Vanessa Simon, the church’s history combines with its ministries, parishioners and pastor to keep her driving from Allen, Texas, a half hour away, for Sunday worship and even midweek activities.

“A lot of reasons to love St. Paul,” she said.

This article first appeared on February 16, 2017, in UMNS

Published: Wednesday, March 8, 2017