The Car Keys, the Finances and Conversations Often Avoided

Missy Buchanan’s “Aging as a Family Affair” seminar reveals what seniors and adult children want each other to know

“Talk now. Talk often.” These four words are huge if you are dealing with an aging parent or you want your adult children to understand your concerns about old age.

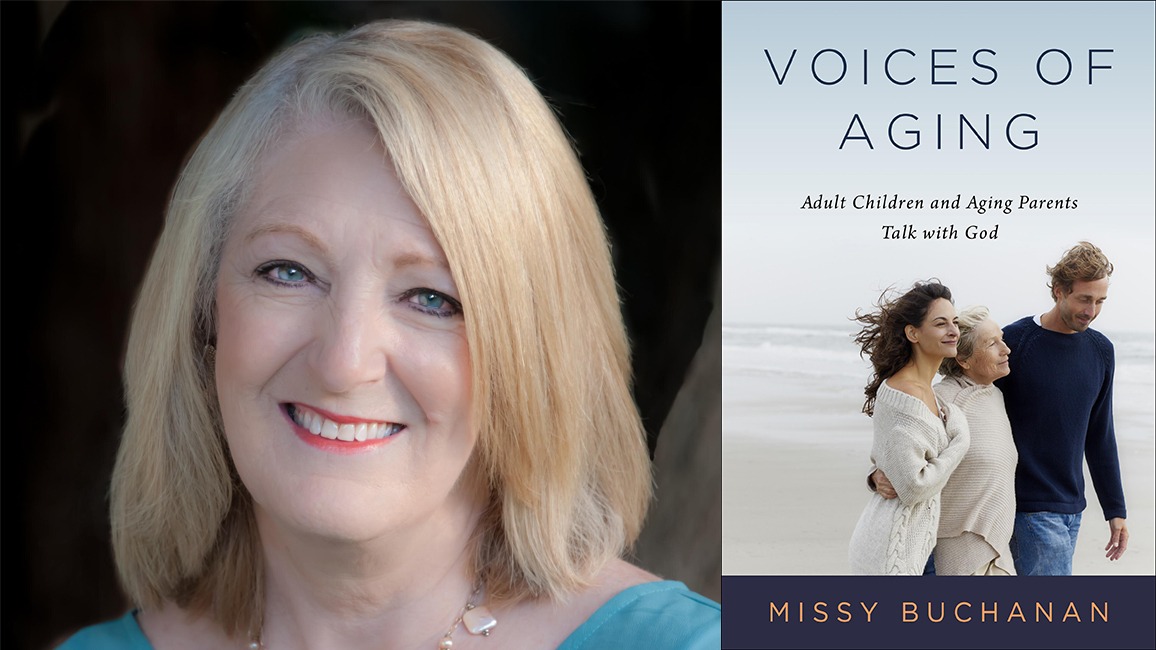

It’s the mantra of Missy Buchanan, author on aging and advocate for older adults. She believes in the importance of adult children talking frequently with their aging parents. She will present a seminar on “Aging as a Family Affair” on April 22, 2017, starting at 9:30 a.m. at Trinity UMC in Duncanville.

Here is a Q&A on issues families face as loved ones age. Answers have been edited for clarity and brevity.

It seems that so many families don’t really think that aging is a family affair or even that parents are going to get old one day and kids are going to have to jump in and do something.

That’s totally true. Life has changed. I grew up with my grandparents living with us. But today, families are so scattered and that complicates things. Think of a pendulum that has the little balls hitting each other. When one ball knocks the other one, there’s a reaction. So when your older mom falls and is hospitalized, it impacts your life. You’re either going to have to take off work or put things you had planned on hold. If she has to go to rehab or if you have to make decisions because she can no longer live at home, what are you going to do? I just found that a lot of families are not talking about it.

How did you become an advocate for seniors?

In my home church, I started getting requests from several middle-age Sunday School classes to talk to them. They told me they realized that half the names on their prayer lists were their aging parents. That was a tough reality for them to accept. But in our youth culture, people don’t want to talk about aging. And when they do talk about aging, they want to frame it in the positive. But we’re still going to age. Our bodies are still going to wear out if we live long enough.

The purpose of Aging as a Family Affair is to bring the generations together. Oftentimes when I speak to senior adult groups, they say, “I wish my kids were here to hear this.” That tells me they’re not talking. I had one lady buy four or five copies of my book Living with Purpose in a Worn-Out Body. I autographed them all and thought they were probably for her neighbors or friends, and she said, “Oh no. These are for my children. They don’t know what it’s like to get old, and I can’t make them understand.” That was very insightful for me.

Many of us are in churches with older congregations. When the teens go to college, often they don’t return to the church they grew up in. How can we change that?

That’s another thing that I hope will come out of this. Several years ago, I got on Twitter because I wanted to communicate with the younger ministers. I wanted to know: Where are they talking? Well, they’re talking on Twitter. There was a young minister who made the comment, “What do I do with all of the walkers and wheelchairs in the narthex? They’re a big turnoff to young families who are coming to church.”

So I had a private discussion with him to stop and think about what that says to older adults who probably had to get up at 4 a.m. because it takes them a lot longer to get to church. But if we do need to move the walkers so they don’t clog up the area, that’s fine. In our church, the ushers are very good about getting people to their seats. They take the walker or wheelchair to the back of the church and bring it back out at the end of service.

It might be a good idea to have the acolytes help and get to know the older people by name and find out something about, say, Mrs. Jones. The point is: We’re in such a youth culture in our churches. This is not to slam our efforts to reach out to young people — we desperately need them, but not to the exclusion of older people. God is interested in old and young, not just one or the other. It’s an intergenerational opportunity just waiting to happen.

At what point should you step in with your parents? Should you wait until you see their health failing? Or just because they’re aging, should you start to find out about Mom and Pop’s finances or what their ideas are for the future?

I say “Talk now. Talk often.” Part of it is because middle-age and younger adults are hesitant to talk to parents. I had young woman tell me her father, who was in his 80s, had tried to talk to her about his financial situation to explain where things were. And she said, “I was like, ‘Dad, I don’t want to talk about it,’ and he died a week later. That was such an eye-opener, I could kick myself because he wanted me to have that information. And instead of me accepting that, I was in denial that nothing was going to happen.”

It’s hard to watch our aging parents change. I remember the day my dad asked me to change a light bulb in a ceiling fan. And my dad was 6-foot-6 and could do anything. He could fix anything. Yet it was a point in his life where it was too difficult for him to reach over his head and change a light bulb.

As sons and daughters, we need to be aware of those things. Both generations need to have the conversations and make it easy. The next book I wrote was Voices of Aging. I wrote it specifically to try to help each generation understand what the other is feeling. On one page you’ll have the topic of driving where the adult child says, “Why can’t Dad understand that he’s going to run over somebody? He hit the mailbox. What if he hurt a child? Why is he being so stubborn?” And these are valid questions.

On the other page is the same topic, but from the parent’s perspective: “Why can’t my children understand that once I give up the keys to the car, my life is going to change forever? They say they’re going to be here to take me places, but they’re busy, and they’re not going to be able to do it. Why can’t they understand this is my last shred of independence?”

If only we can just begin to stand in each other’s shoes and try to understand, and then bring God into the conversation. There’s a lot of secular literature on things to do on this topic, but it should be different for us as Christians. We should be the ones who are modeling it well for the rest of the world. But we’re not doing a very good job of that.

Do you think some people are afraid of caregiving?

I’ve learned that people don’t always understand the whole idea of caregiving. They think they have to have their mom or dad living with them, and that’s not true. A caregiver is one who has that person’s best interests in mind and is helping to make the decisions for that person, but not totally for them. I was caregiver for my parents even though they lived in senior care. I would go over there every day to check on them and help them.

How do you work out situations with siblings?

It’s really hard. You get so many family dynamics. If you don’t have good relationships with your siblings in general, all of this just makes it that much more difficult. In my book Voices of Aging, I have one devoted side-by-side pages just about siblings. It’s going to be different in every situation. That’s all the more reason to talk about it together now. That’s why I say, “Talk now. Talk often.” Not to make decisions for them, but to be involved jointly. The adult children sometimes think, “We know best,” and they don’t confer with that aging parent. That’s why it’s got to be a family affair. And for those families that are dysfunctional, start conversations with a prayer!”

Published: Tuesday, April 4, 2017