Knowing Your Personality Type Can Ease Your Spiritual Journey

NTC’s Suzanne Stabile is part of an Interpreter story on how people explore spirituality differently

St. Francis of Assisi found his spiritual center among the birds of the air and the lilies of the field. St. Julian of Norwich took off alone to have mystical visions of Jesus in private prayer. St. Benedict of Nursia established a balanced pattern of living and praying to glimpse the glory of God.

Through the centuries, sinners now seen as saints drew away from the world, turned to worship in lay and clerical communities, sought simplicity in daily life and work, and encountered God in contemplative prayer, art and song.

Similar winds of spiritual formation blow today through United Methodist ministries, churches and seminaries. The paths followed by these 21st-century pilgrims take many shapes. So do their rules, patterns of prayer, psalm and song, and their psychological and theological systems. Some are rooted in historical Christianity. Others draw on practices with different religious, philosophical and psychological overtones.

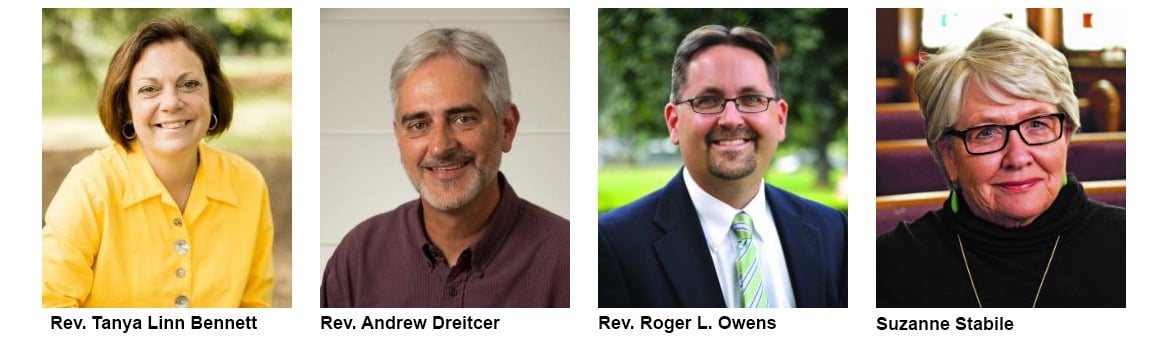

“God created us the way we are, and we’re all different,” said the Rev. Roger Owens, a United Methodist and associate professor of Christian spirituality and ministry at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania. “We shouldn’t be surprised that the different aspects of our personalities are the ways through which we can relate to God.”

Spiritual Self-Awareness

Suzanne Stabile, author and speaker, instructs others in deepening their spiritual journeys through the Enneagram, a system of classifying personality types based on a nine-pointed star-like figure. The figure is inscribed within a circle in which each of the nine points (numbers) represents a personality type and its psychological motivations.

“It’s not about learning differences,” said Stabile. “It’s about different ways of seeing the world.” She oversees The Micah Center, part of the Trinity Life in the Ministry program that she founded 31 years ago with her husband, the Rev. Joseph Stabile, an associate pastor at Highland Park United Methodist Church in Dallas.

With the Enneagram, Stabile said, people learn that an imbalance exists within them. Once identified, it can be dealt with. Stabile sees applications for the Enneagram in church life as congregations work to grow the programs they offer.

“If we offered the right kind of programming that people could use for the spiritual journey towards transformation, it would include programming that brings up thinking, brings up doing and brings up feeling for various people. Then we would actually be building a foundation for all the other things that we want to happen,” she said.

Offering an example, she said, “Eights on the Enneagram are passionate, but they are feeling repressed. And fives on the Enneagram have a limited amount of energy every day. And every social encounter costs them something. Fives and eights are never going to be comfortable sitting around a table and sharing with other people some story from their lives or their feelings. If you want to build a relationship with fives and eights, go build a house for Habitat for Humanity.” The building or other service is also a prime way for five and eights to grow spiritually.

Stabile sees a crying need for self-study. With Ian Morgan Cron, she co-authored The Road Back to You: An Enneagram Journey to Self-Discovery (InterVarsity Press). But why use the Enneagram to grow one’s self-awareness? “Your Enneagram number is not determined by your behavior. It’s determined by your motivation for your behavior,” she said.

Practices and Personalities

Some Christians flourish in small, intimate groups. Some prefer solo seeking, finding a deeper relationship with the divine in quiet contemplative prayer, in meditation and soulful walking. Still others need regular community, preaching, the joy and peace of worship and frequent fellowship with others. Others want a straightforward path, turning to online tools such as The Upper Room’s guide to spiritual types found in the Living Prayer Center section of the website.

Taking the quiz reveals whether one is a:

- Sage, thinking or head spirituality;

- Prophet, servant and world changer;

- Lover, spirituality from the heart or emotions; or a

- Mystic, someone who finds God in silence, solitude or contemplation.

Gifts and talents vary; the need for prayer, worship, community and spiritual growth always remain. Most important is recognizing that “different sorts of prayer practices or styles do meet different needs for different people and also for people at different points in their lives,” said the Rev. Andrew Dreitcer, director of spiritual formation at United Methodist-related Claremont School of Theology in California.

Those styles meet participants’ needs and form people in particular ways.

“If you look at Catholic religious orders, their frames have a certain intentionality about them, about where they want you to end up,” he said. “Then they have certain formative practices. The Benedictines were more traditionally focused on silence and the absence of words and images as ways to get closer to God. Their prayer style emphasized silence and repetitive psalms that moved you into silence and into interior stillness and an absence of imaginative and conceptual activity.”

Prayer: The Essential

Whatever the form or theory, the experts agree that each individual can deepen his or her relationship with God through self-understanding and the study and practice of prayer. For example, some of us learn best through listening to music, doing artwork and singing. Others access paths to God through thinking or deep meditation.

Some might digest a Scripture passage through lectio divina, a Benedictine practice, intended to promote communion with God through reading, meditation and prayer.

Another style is linked to St. Ignatius Loyola. When a retreatant came, St. Ignatius would invite him or her into “contemplation.” That meant the retreatant used the senses to reflect on a Gospel passage imaginatively and utilizing seeing, hearing, tasting, touching and smelling so that the Gospel scene became real and alive.

Both practices and many, many others still are used in group and private retreats. Many retreatants also want spiritual direction, in which a person augments private prayer and worship with regular meetings with a spiritual director — not a therapist or coach — but a trained companion to help one grow closer to God.

At Drew Theological Seminary in New Jersey, the Rev. Tanya Linn Bennett said students examine a cross section of traditions in spiritual formation and field education classes and in her sociology of religion class. Those include using the Enneagram and the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, an introspective self-report questionnaire designed to indicate psychological preferences in how people perceive the world and make decisions.

“It’s such an individual thing,” said Bennett, Drew’s associate dean for formation and vocation. “But then they probably want also to have the opportunity to practice a number of the very traditional and ancient spiritual disciplines.” She sees value in both the Enneagram and Myers-Briggs for understanding which practices may be helpful.

Movement prayer, music, singing, liturgical dance and iconography are more popular. “We know for example that singing is good for your health and that being part of a group that meets regularly to sing together improves your health,” she continues.

Sometimes prayer forms itself. In one of Bennett’s formation classes, students focused on fasting. One suggested fasting from electronics, while others said they’d done that. So the one intent on fasting “actually brought a love feast,” Bennett said, “symbolizing that we too often fast from being with the people who enrich our spiritual lives.”

The trick, say the experts, is to explore prayer forms, recognizing that the prayer style we need — like the worship style we need — links to different life experiences. “People change,” Dreitcer said.

Citing the experience of deep grief, he explained, “Let’s say we have someone where their grief is taking the form of just the inability to feel any comfort. This happens to people who are lonely. … It’s important for them to look for a prayer style that allows them to rest in a loving presence. That could involve imagining God as a loving presence. For some that form might be a warm light, for others, being held in the arms of a loving mother or simply walking with Jesus.”

Spiritual Direction Helpful

Owens stressed the value of finding a spiritual director. “These are people who sit with you to discern the presence of God in your life. When you begin to pay more attention to yourself and your life, you can discern the next step to growth in God,” he said. “So paying attention to personality type can be part of that — who you are and how God wired you.”

Many seminarians today will be bi-vocational clerics, Bennett notes. She sees herself training people to be “public theologians” who will discover their life calling in multiple settings and assist others to do the same. Dreitcer added that since Claremont’s program is interfaith, his students draw from many religious traditions. “They are not only Christians, but also Jews, Buddhists, Muslims and others,” he said.

Regardless of their tradition, he continued, “the students tend to discover that to get through the first year of seminary, it becomes very important for them to find some sort of spiritual practice and indulge in it, even if they’ve never done that before. Most of them are engaged in some way to ‘change the world,'” he said. “And they’re burned out. They find out that these (spiritual) practices sustain them not only in their lives, but in their studies.”

As it was in the beginning, so it still is. The paths to wholeness, prayer and communion differ. The goals stay the same: spiritual growth and intimacy with God.

This article by Cecile S. Holmes was originally published on Interpreter Magazine.

Cecile S. Holmes is a longtime religion writer and heads the journalism sequence for the School of Journalism and Mass Communications in the College of Information and Communications at the University of South Carolina.

Published: Tuesday, May 2, 2017