Don’t White-Wash Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Message

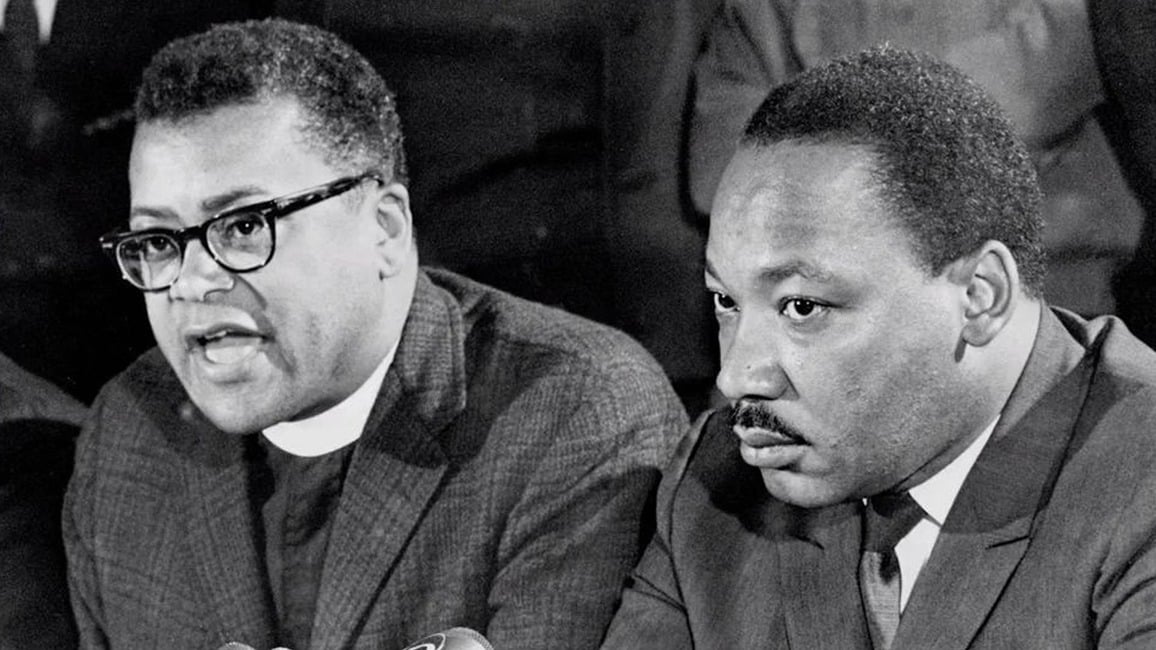

Rev. James Lawson and Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King

Rev. Andrew Fiser learned the Civil Rights Movement was about more than civil rights. It was the Black Freedom Struggle.

We have the option every year to do one of two things each Martin Luther King Day. We can either white-wash the legacy of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., or we can hear the fullness of this preacher’s and prophet’s challenge to America. The people who joined King in the struggle offer insights into the fullness of his message. I draw your attention to a United Methodist who knew him as his friend Martin. Rev. James Lawson taught my first Vanderbilt Divinity School class: “The Non-Violent Struggle.”

We have the option every year to do one of two things each Martin Luther King Day. We can either white-wash the legacy of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., or we can hear the fullness of this preacher’s and prophet’s challenge to America. The people who joined King in the struggle offer insights into the fullness of his message. I draw your attention to a United Methodist who knew him as his friend Martin. Rev. James Lawson taught my first Vanderbilt Divinity School class: “The Non-Violent Struggle.”

As recounted in David Halberstam’s The Children, Lawson met King in 1957 and King encouraged him to postpone his academic career and join the struggle. “Come South now,” he said. Lawson was a student of Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violence and a Korean War draft-resister who served 14 months in jail for refusing to agree that the state had the right to coerce anyone to do violence.

Lawson became the primary trainer and strategist for the non-violent direct action campaigns across the South. In Nashville, Lawson enrolled at Vanderbilt Divinity School and served as a Methodist pastor in the area. Lawson was a main catalyst for the Nashville successful sit-ins, which drew together local students like Ambassador Andrew Young, Rep. John Lewis and Diane Nash. Many of the young leaders Lawson trained in Nashville went on to lead the Freedom Rides and movements around the country.

Lawson went on to pastor Centenary UMC in Memphis, which served as an organizing hub for the Sanitation Workers’ Strike of 1968. Lawson prevailed upon King to come to Memphis as King prepared to launch a nationwide, multi-racial Poor People’s Campaign. It was there in Memphis, fighting for the safety and fair wages for sanitation workers, that Lawson’s friend and mentor, Martin, was assassinated. Years later, Lawson led the memorial service for King’s assassin, James Earl Ray, at Centenary as an act of redemptive non-violence.

What Lawson taught our classes is that what we label the Civil Rights Movement was about far more than civil rights. It was the Black Freedom Struggle. It was a part of, but not an end to, a moral awakening to the sicknesses affecting all Americans: racism, sexism, militarism and income inequality. King was not welcomed by many churches or leaders when he was alive. And when his work expanded to include denouncing the war in Southeast Asia and a call to end poverty for all in America, King was further reviled as a communist.

The Poor People’s Campaign launched with minimal success after King’s death. But the work has re-started as The Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival by The Red Letter Christians and Bishop William Barber II and Rev. Liz Theoharis. The campaign, which was hosted in November by St. Luke “Community” UMC in Dallas, is calling for moral action to combat Systemic Racism, Poverty & Inequality, Ecological Devastation, the War Economy & Militarism and the nation’s distorted morality.

Sometimes we wonder what we would have done during the Civil Rights Era. The truth is that we’d be doing what we are doing now. And if you are disappointed by that realization, as I have been, then it’s time to wake up and join the struggle. Sign up to get involved in the Poor People’s Campaign. Read King’s final and often forgotten book Where do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?

It is my hope that we’ll remember the challenge in King’s words, a challenge that millions of women and men embodied as part of an often unpopular struggle for righteousness then and now. May we be called out of our complacencies to follow Jesus Christ in ways that are likely to upset those we know and love.

Published: Tuesday, January 8, 2019