Bearing Witness At The U.S.-Mexico Border

Doug Reader, Marsha Gordon, Susie Spellman, Texas Impact's Whit Bodman, Karen Shuey, Wendy Campbell, Kellie Hooker and Kay Dial stand in front of the border fence.

Lovers Lane UMC's Kay Dial went to observe and ended up putting her nursing skills to the test

What was really going on at the U.S.-Mexico border? The United Methodist Women at my church, Lovers Lane UMC, wanted to know. The Courts and Ports program offered a way to observe Rio Grande Valley courtrooms and at border crossings. Eight of us from Lovers Lane made the trip.

On March 18, 2019, we visited the U.S. Courthouse in Brownsville, Texas. While there, we spoke with court clerks and officers, public defenders, prosecutors and members of other agencies, including Customs and Border Patrol (CBP). Inside the courtroom 48 young men, six women, four Bangladeshis and a man named Victor Hugo were arraigned before U.S. Magistrate Judge Ronald G. Morgan. Their crimes were varied, including “possession with intent to distribute a controlled substance” and “human trafficking." Most were charged with “entering at a place other than a legal crossing." Most were from Mexico, a few from Honduras. None were claiming asylum.

In April 2018 the current administration ordered that anyone crossing the U.S.-Mexico border between ports of entry be prosecuted “to the full extent of the law." At the same time, ports of entry were closed. A “metering” system was activated, allowing one or two families to cross the bridge each day. Eleven months later when we arrived, a choke point had formed. Responding to news that the border was closing, immigrants had come in greater numbers. Now the flow was backing up as people spilled into the river, the desert and streets throughout the Rio Grande Valley. Results of this policy change were also visible in the crowded courtroom.

With hands and feet shackled, the defendants stood together and answered as a group when questions were asked in Spanish.

As the prosecutor explained later, instead of being deported after an immigration hearing, now these cases must be heard in a criminal court as well. Accordingly, thousands of immigrants are now processed each week through both our criminal district courts and the immigration courts along our border.

The atmosphere was somber; Judge Morgan, respectful.

“Have you met with a lawyer?”

“Were the charges explained to you?” and then, individually they were asked, “And how do you plead to the complaint? Guilty or not guilty?”

All defendants pled guilty.

I was standing in the middle of a humanitarian crisis.

After the proceedings, the prosecutor and public defenders told us their jobs had become much more difficult because of the volume of people funneled through this system. And while additional judges from around Texas were brought in to manage the case load, the system was overwhelmed, the backlog growing.

When we asked about the Bangladeshi gentlemen in the courtroom and why they were taken aside, the prosecutor shrugged, “Honestly? We can’t afford interpreters for everyone. Their case will probably be dismissed because of it.”

While waiting outside the courtroom, I talked with the Border Patrol officer accompanying these prisoners. His parents were naturalized U.S. citizens, but his mother crossed back into Mexico for his birth, giving him dual citizenship

He laughed, “Most people do it the other way around.”

This young man usually worked at the port of entry, inspecting vehicles. He took great pride in describing his work keeping our border safe, but also expressed frustration at not being able to do his job; reminding me that most of the contraband flowing in and out of Mexico comes in cars and trucks. In the week following our visit however, an additional 750 Border Patrol officers were pulled from ports of entry and reassigned to help process, transport and care for the influx of immigrants.

Center Overworked

Later that day we visited the Catholic Charities Respite Center in McAllen, Texas, and witnessed the effect of the border crisis on this local nonprofit group and its operations.

Our group ducked into the low-slung building tucked in a residential neighborhood. As we waited for a tour of the facility, Volunteer Coordinator, Hermi Forshage, stood before us in the small entryway, directing a maelstrom of bodies, answering questions, translating and ushering groups of people past us, out the front door and into vans. Between interruptions she explained that their purpose is to give temporary respite to people.

“We commit ourselves to enhancing the dignity of life by working for peace and justice,” Forshage said.

From the crowded reception area, I saw a line of people snaking down a central hallway, out of view. Hundreds of people were crammed inside this former nursing home. The rain was driving in dozens more who had been clustered outside.

We learned that some would be here for a few hours, some a few days. All had been released from a detention center after contacting family inside the U.S. Now, they either had tickets or were waiting on bus tickets to join those relatives. Hopefully, with an immigration hearing somewhere nearby.

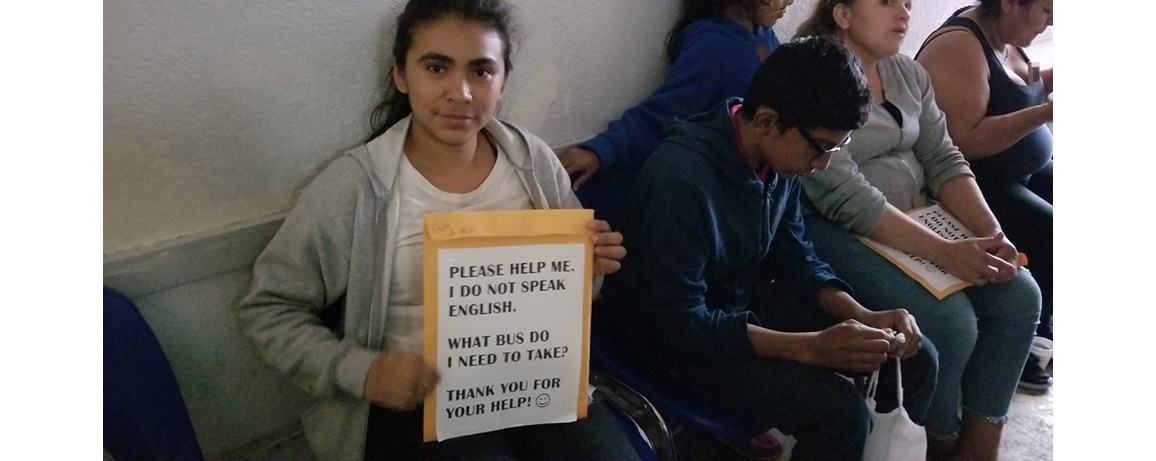

Many of them in line near the door held a small sack and an envelope that read “PLEASE HELP ME. I DO NOT SPEAK ENGLISH. WHAT BUS DO I NEED TO TAKE? THANK YOU FOR YOUR HELP!”

“Some of these people will travel for two days and change buses several times,” Forshage said.

From outside, I heard the squeaky brakes of old school buses rolling to a stop. Within seconds, a stream of new arrivals began filing through the door.

A nun approached Forshage. They spoke briefly, then she addressed us.

“We just received a call from ICE. They released over 850 people today onto the streets of McAllen. That is what we’re seeing. Tomorrow they will release another 1,000. They will come here.”

Turning back to the nun, Forshage began, “We need more vans, drivers . . .”

They continued their conversation and melted into the crowd.

I noticed our group unclustering, blending in, being pushed forward into the mass of people. Apparently, we had landed the middle of a disaster layered on top of a crisis. The two Spanish speakers in our group moved to a nearby desk and began assembling paperwork for the immigrants.

My limited medical Spanish was beyond rusty and there didn’t seem to be anything I could do, except move with the crowd. We were here, after all, to see and observe. I took a deep breath and followed the line of people, shuffling, dodging, being pulled along a human conveyor belt. In a single line hugging the left side of the hall, a few of us headed back, past the kitchen where volunteers ladled soup and assembled hot dogs. As we moved in one direction toward the rear of the building, a larger line – 4 and 5 people across – faced forward, bumping into each other in passing, breathing the same damp air, inching ahead, and ultimately, out the front door.

Most of the immigrants were young – families with small children. Preteen boys dodged in and out of line, fetching water, diapers, translating for adults. There were few men, a handful of elderly, but mostly women and children. And more pregnant women than one would expect.

Past the common areas the hallway was lined with patient rooms, originally built to hold two twin-sized beds and a chair.

But now the floors were covered with gym mats, which were strewn with people; babies, young women, teenagers and toddlers. They had no belongings or possessions with them, as if they had fled a house fire in the middle of the night. In room after room, I saw clumps of people sitting, lying together on mats; some staring vacantly. No one returned a smile and the babies were uncharacteristically quiet. Looking over the crowd, I noticed that the two-inch heel on my boots put me at 5’4,” eye to eye with most of the men. I towered over the women and teens.

At this point I realized these weren’t the same Mexican immigrants I’d seen in my Dallas mission clinic a few years ago. Those were sturdy working men and women, battling obesity, diabetes and high blood pressure. These people were smaller, thinner and darker. Some of them spoke languages other than Spanish. Were they fleeing years of drought and famine in Guatemala? Were they running from the narco-state of Honduras? Or had they left El Salvador in a hail of bullets? As surely as people fleeing Syria or Yemen, they were refugees. But instead of finding refuge in camps run by NGOs, they were huddled here in the beleaguered city of McAllen.

I was standing in the middle of a humanitarian crisis.

The line of people snaked down the hallway, pulling me until I stumbled out the back door, near a laundry room. Piles of dirty clothes were heaped on the floor. Mounds of clean clothes sat unfolded on a large table. One of two industrial sized washers was working, and two of the four dryers were broken. A teenage volunteer explained that when people arrive, they are offered a shower. Their dirty clothes are taken and replaced with clean clothes recycled from other refugees.

I began to fold and sort, finally taking the clean items to a room where clothes were organized by size and gender. Once finished, I ducked into a small room and joined other volunteers assembling sandwiches that would go into sacks with chips, fruit and water for each person leaving on a bus. As we opened the last loaf of bread, a nun entered with good news: more bread would arrive soon. Of course, we were in a religious facility so there was much talk of God’s goodness and bounty, but at this point, I wasn’t so sure about that, so I moved on.

Bad Medicine

In the back yard, I came upon a small free-standing clinic. Ducking in to look for a restroom, I saw a crowd of people lined up; many with small children. At the head of this line a woman stood behind a table, organizing, passing out nonprescription drugs – cough medicine, Tylenol, Pepto Bismol, Neosporin, vitamins, rehydration packets.

On my way out, as an afterthought, I told her I was a nurse and offered to help distribute these items. I wasn’t signed in as a volunteer and didn’t have a name tag, but under the circumstances, it seemed polite. She summoned a teenage interpreter, and they spoke in Spanish. As I extended my hand in introduction, the teenager held out a spiral notebook, pen and a stethoscope, then pointed to a young boy sitting in a blue plastic chair.

“He is ready. With the sore throat and cough.”

So for the next two hours a stream of patients sat in the little chair before me. Responding to my bad Spanish, and with help from the interpreter, they described their ailments: sore throats, coughs, asthma, stomach upset, rashes and fevers, including a woman with a temperature of 105.3.

I looked into their eyes, ears and throats and listened to their hearts and lungs. I inspected their rashes and asked the familiar questions – How long has it been there? Does it itch? What makes it better or worse? Do you have any other health problems? Any allergies? I dispensed medicine from the meager supply and gave an asthmatic woman a nebulizer treatment with the only compressor available, a small blue whale, meant for pediatric patients. I briefly toyed with the thought that I might be working outside my scope of practice.

I made recommendations to rest and drink plenty of water but couldn’t tell them to call or come back if there was no improvement. I couldn’t even suggest they go to an emergency room if the symptoms worsened. All I could say was “Buena suerte” or “good luck” because if they were lucky, they’d soon be on a bus with a “Please Help Me” envelope.

In the battle against disease transmission, this was the front line. Thousands of people were coming and going. After traveling for weeks and months, they had arrived exhausted and dehydrated. Now, after being detained in crowded and unsanitary conditions, they were headed to cities all over the United States. The situation is ripe for the spread of an epidemic.

According to a report by the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, “in May, 32 migrants tested positive for influenza in a CBP facility in McAllen, Texas, after a 16-year-old Guatemalan migrant detained at the facility died of the disease.” The CDC website says, “Flu activity most commonly peaks in the United States between December and February.” And on August 29, CBP reported 900 cases of mumps in their migrant detention facilities.

“Suffer The Little Children”

The following day we crossed into Matamoros, Mexico, a city the U.S. State Department has designated as a Level 4 – Do Not Travel area. Our group spent the morning talking to nonprofit workers, interviewing refugees and handing out food and supplies to those waiting near the gate. Our planned visit to a nearby shelter was canceled for security reasons.

My friend Kelly and I surveyed the border station just inside Mexico as a light mist fell. We moved under the watchful eyes of masked Marines with automatic weapons. This morning our party of eight had crossed the empty bridge from Brownsville into Matamoros. We were now surrounded by dozens of people milling around on an open plaza. After handing out clothes, food and toiletries, we split into smaller groups and began talking to individuals and listening to their stories

Kelly quizzed one man in Spanish.

“Where are you from?”

“We come from El Salvador.”

“Where are you going?”

“We hope to reach Los Angeles. My wife has a sister there.”

“Do you have a number to cross yet?”

“No.”

Senor Hernandez, his wife Karla, and their two boys, Jose, 5, and Daniel, 10, left a middle-class life in San Salvador on December 15. They traveled through Guatemala, then to Tapachula, the southernmost city in Mexico. They waited three months for Mexican visas. Then, instead of paying a coyote for transport, moved on their own.

Senor Hernandez, his wife Karla, and their two boys, Jose, 5, and Daniel, 10, left a middle-class life in San Salvador on December 15. They traveled through Guatemala, then to Tapachula, the southernmost city in Mexico. They waited three months for Mexican visas. Then, instead of paying a coyote for transport, moved on their own.

“I want to do this right,” Senor Hernandez continued. “We need to cross the border legally and make a claim for asylum.”

As they talked, Jose inched closer to my side. He took a peanut from his small bag of trail mix and thrust it toward me.

“Para ti!” he said, placing it in my hand.

“Gracias, Jose,” I responded, and popped the nut into my mouth.

Kelly translated as Mr. Hernandez told their story. The previous night they arrived in Matamoros and within hours their backpacks and belongings were stolen. But they had seen worse.

“San Salvador is bad,” Senor Hernandez said, patting Jose’s head. Then nodding toward Daniel, “It’s too dangerous for my boys.”

Kelly and I understood. News reports from the last decade back up his claims. Corrupt government, erosion of the rule of law and violent street gangs have transformed El Salvador into a tropical hellscape. A torrent of illegal weapons fuels the fire, making its capitol, San Salvador, one of the deadliest cities on earth. Two well-scrubbed teenage boys stood nearby.

Mr. Hernandez acknowledged their presence. “They are traveling with us . . . for safety.”

Now this group waited on the wrong side of the Rio Grande, knowing it may be months before they can cross.

Under the “metering” system, each day a Mexican official hands out two numbers to the people gathered near the bridge. Only then can they approach the bridge and cross. No one understands the arbitrary rules that change frequently, and because it’s Mexico, an exchange of money is most likely involved. Occasionally, everyone is forced to evacuate the plaza, forfeiting their place in line. Some give up and try to cross elsewhere, like the river or desert. Recent insider accounts reveal that during this time, President Donald Trump suggested shooting immigrants in the legs to slow them down as they approached the border.

While Kelly and Mr. Hernandez talked, Jose took another peanut from his small bag and placed it in my hand. I popped it into my mouth and gave him a wink.

“It may be months before they get a number,” Kelly translated. “But he has faith and hopes they can cross soon.”

She offered to pray before we left, so the six of us embraced. Senor Hernandez gathered his family close and motioned for the two teens to join us. They stepped forward and draped their arms around our shoulders. Kelly prayed in Spanish, thanking God for his blessings and asking for grace and mercy for the Hernandez family. She asked for safety and security and that God be with them as they traveled, seeking a better life.

When Kelly closed her prayer with “En el nombre de Jesu Christo,” we all said, “Amen,” together. It could have been my imagination, the vibration of our voices, or something else, but I felt an energy and sense of connection between us that made me want to hold onto these people.

Jose returned to his packet of trail mix. As we began our goodbyes, he scooted closer, digging deep into the package, bidding me to wait. Then he produced another morsel. But this time it was something more precious than a peanut. It was a piece of chocolate.

As he dropped it into my hand, I felt the weight of privilege and the burden of responsibility. Yet there was nothing I or my fellow volunteers could do. Despite our social connections, college degrees, religious credentials, white skin and unlimited Visa cards, we were powerless to help this family.

As he dropped it into my hand, I felt the weight of privilege and the burden of responsibility. Yet there was nothing I or my fellow volunteers could do. Despite our social connections, college degrees, religious credentials, white skin and unlimited Visa cards, we were powerless to help this family.

Our group trudged back across the bridge to Brownsville. While standing in a small park, we recorded videos of what we’d seen while it was still fresh. We discussed what we could do – volunteer more that day at another center, send donations and supplies for aid groups and organize a collection drive. Within weeks we had done all these things, knowing there was still more work ahead. According to the Texas Tribune, there are “now an estimated 2,000 people, many of them children,” camped at this location.

We had to leave the daily monitoring to locals – law enforcement, relief workers, judges and border patrol – angered by the chaos and at seeing their community stretched beyond the breaking point.

We had to leave the search for facts to reporters, local and national, who relentlessly cover this story. We had to leave the lawsuits over this matter to human rights groups and immigration lawyers.

Our job was to observe and report back to our congregation, our friends and families, our neighbors, and anyone else who would listen. Which we did, though for months afterward I was confused by the magnitude of what I’d seen and hesitant to raise my voice in the ongoing conversation. But I signed an agreement to bear witness. So . . .

For the 59 men and women shackled in the courtroom,

For the thousands of people crammed into the respite center,

For the Hernandez family, who might still be on the other side of the bridge,

And for Americans who, like me, wonder what’s happening on our border,

This is what I saw.

Kay Dial, MSN, RN, is a member of Lovers Lane UMC

Published: Tuesday, November 19, 2019