50 years ago, compromise was crucial in forming UMC

April 23 marks the anniversary of the merger of Methodists and United Evangelical Brethren in Dallas

The year 1968 convulsed with assassinations, riots, war in Vietnam and student protests against that war.

But at a time of upheaval, a group of Wesleyan Christians peacefully and joyfully came together in Dallas.

On April 23, 1968, two bishops followed by two children, two youths, two adults, six ordained ministers, two church officers and finally all 10,000 people present joined hands and repeated in unison:

“Lord of the church, we are united in thee, in thy church, and now in The United Methodist Church. Amen.”

With those words, the 750,000-member Evangelical United Brethren Church and the 10.3 million-member Methodist Church became one. The merger also marked the dissolution of the Methodist Church’s racially segregated Central Jurisdiction.

“It felt like the restoration of the Methodist movement,” said Rev. Joseph Evers, 91, a Methodist delegate to the 1968 Uniting Conference who now lives in Quincy, Ill.

The path to The United Methodist Church faced roadblocks. Bishops from both denominations in 1957 identified possible impediments to union, said Rev. Ted Campbell, church history professor at Southern Methodist University’s Perkins School of Theology.

One issue was that the Methodist Church gave bishops life tenure while the Evangelical United Brethren had term limits. The list also included the size difference between the two churches, the manner of selecting district superintendents, overlapping church agencies, and finding a name that honored the heritage of both denominations.

To make the union happen, the two denominations compromised on practices, adopting some from Methodists and others from the Evangelical United Brethren.

The Evangelical United Brethren ultimately made abolishing segregation a condition for union, said Rev. J. Steven O’Malley, a EUB pastor. Four years before the union, Methodist conferences within the Central Jurisdiction began transferring to geographical jurisdictions.

“By 1964, there were just so many of us who thought segregation was wrong and that the Central Jurisdiction was an anomaly in the Methodist Church because our theology didn’t support segregation,” said Evers.

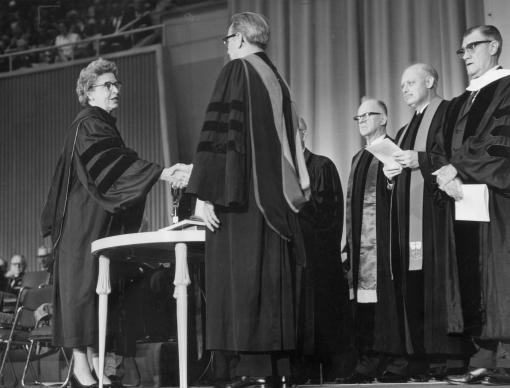

The 1968 union also ensured women the right to be ordained and have full clergy rights, said the Rev. Patricia Thompson, author of “Courageous Past — Bold Future: The Journey Toward Full Clergy Rights for Women in The United Methodist Church.”

However, the church sometimes struggled to live up to its teachings.

Retired Bishop Susan W. Hassinger, who came from the EUB side, was ordained in 1968. She waited two years for her first appointment, which was only part-time.

Hassinger and other church leaders say the denomination can learn from its union. Those lessons seem especially relevant as the church prepares for a special General Conference in 2019, when delegates will face the issue of homosexuality.

“People had to listen to each other across differences and learn how to value the other,” said Hassinger, now bishop-in-residence at United Methodist Boston University School of Theology.

O’Malley said the church can benefit from its Evangelical United Brethren heritage by taking an approach aimed at reconciliation and peace.

Heather Hahn is a multimedia news reporter for United Methodist News Service. Contact her at 615-742-5470 or newsdesk@umcom.org.

Published: Monday, April 9, 2018